VuwCTF 2025

I played VuwCTF 2025 with tjcsc. We got 5th place!

Challenge: string-inspector

Category: Reverse Engineering

Author: maxster

Flag (intended): VuwCTF{0027094767331}

Alt flag I stumbled on first: VuwCTF{1720554767331} (binary accepts it, but the author marked it unintended)

My initial read / first impressions

There was only one file given: a binary. I always start by seeing what I’m dealing with:

chmod +x inspector

file inspector

# ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, statically linked, stripped

Running it with no arguments:

./inspector

# Enter flag as argument to this program

So it expects the flag on the command line. Before diving into a disassembler, I like to skim the readable parts:

strings -n 6 inspector | head

# Flag rejected!

# Flag accepted!

# Analyzing flag: %s

# VuwCTF{

# 0000000000042

# 0319993

The VuwCTF{ plus the two numeric strings (0000000000042 and 0319993) looked like check constants. My instinct felt like the flag would be VuwCTF{<digits>} with some math involving those numbers.

Recon: what does it actually do?

First, I tried a dummy flag:

./inspector VuwCTF{testflag}

# Analyzing flag: VuwCTF{testflag}

# Flag rejected!

To see how it rejects, I watched the syscalls with strace:

strace -f ./inspector VuwCTF{0000000000042} 2>&1 | head -n 40

The interesting part of the trace:

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "VuwCTF{0000000000042}"], ...) = 0

...

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000000000042", "0000000"], ...) = 0

...

write(1, "Flag rejected!\n", 15) = 15

After checking the wrapper, it immediately re-executes itself with three arguments: the digits-only string and a helper string of seven zeroes. That’s very useful info! The real verification logic runs in this “three-argument” mode, and the initial run is just a wrapper.

Disassembly: wrapper mode

Opening it in GDB and disassembling around the entry point (0x401790):

gdb -q ./inspector

(gdb) disassemble 0x401790,0x401950

The wrapper logic (as I understood it) was:

- If you don’t give at least one arg, it prints “Enter flag…” and exits.

- In this mode it wants exactly one arg.

- It checks:

- total length is 21,

- the string starts with

VuwCTF{and ends with}, - the 13 characters inside are all digits.

- On failure, it prints “Flag rejected!”.

- On success, it calls:

execve(argv[0], [argv[0], digits_only, "0000000"], NULL);

Then it exits. So the first run is just input validation and argument rewriting.

The real checker: manual long division

The second run (with digits + seven zeroes) is where the work happens. Disassembling around 0x4018d0 to 0x401a40 shows a hand-rolled long division on the decimal string:

- It divides the decimal string by the constant 84673. There isn’t anything fancy here. The code literally iterates the characters like you would do on paper: bring down a digit, compute a quotient digit, carry the remainder.

- While dividing, it builds two strings:

- A remainder string, zero-padded to 13 digits.

- A quotient suffix string holding the last 7 digits of the quotient.

- When done, it compares those strings against hard-coded targets in

.rodata:- remainder must be

0000000000042(i.e., remainder 42), - quotient tail must be

0319993(i.e., quotient ≡ 319993 mod 10^7).

- remainder must be

- If both match, it prints “Flag accepted!”, otherwise “Flag rejected!”.

You can see the constants directly:

objdump -s -j .rodata inspector | sed -n '0x7f040,0x7f080p'

# shows "VuwCTF{", "0000000000042.", nearby bytes

gdb> x/s 0x47f052

# "0000000000042"

gdb> x/gx 0x401989

# 0x33393939313330 -> little-endian ASCII "0319993\0"

The multiple execve calls in the earlier strace make sense now: the binary keeps re-launching itself while it walks the digits and builds those strings.

Solving the math

Let N be the 13-digit number inside the braces.

From the code we need:

N ≡ 42 (mod 84673)⌊N / 84673⌋ ≡ 319993 (mod 10^7)Nrenders as exactly 13 decimal characters. Because the binary keeps the literal string, leading zeroes are allowed and significant.

Write N = 84673 * Q + 42, where Q ≡ 319993 (mod 10^7).

So Q = 319993 + 10^7 * t for some integer t ≥ 0, and:

N = 84673 * (319993 + 10_000_000 * t) + 42

I checked small t with a tiny Python snippet:

mod = 84673

req_q = 319993

req_r = 42

for t in range(0, 5):

n = mod * (req_q + t*10_000_000) + req_r

s = f"{n:013d}"

print(t, n, s)

Output:

0 27094767331 0027094767331

1 873824767331 0873824767331

2 1720554767331 1720554767331

All three are 13 characters long. Because the checker treats the decimal string literally, all three pass the division checks.

The detour: unintended flag (not orz, braincell loss)

I initially tried the “clean” non-leading-zero version:

./inspector VuwCTF{1720554767331}

# Flag accepted!

I submitted that to the CTF website, but it did not work… So I did what any dumb person would do: proceed to doubt myself when I literally had two other possible answers.

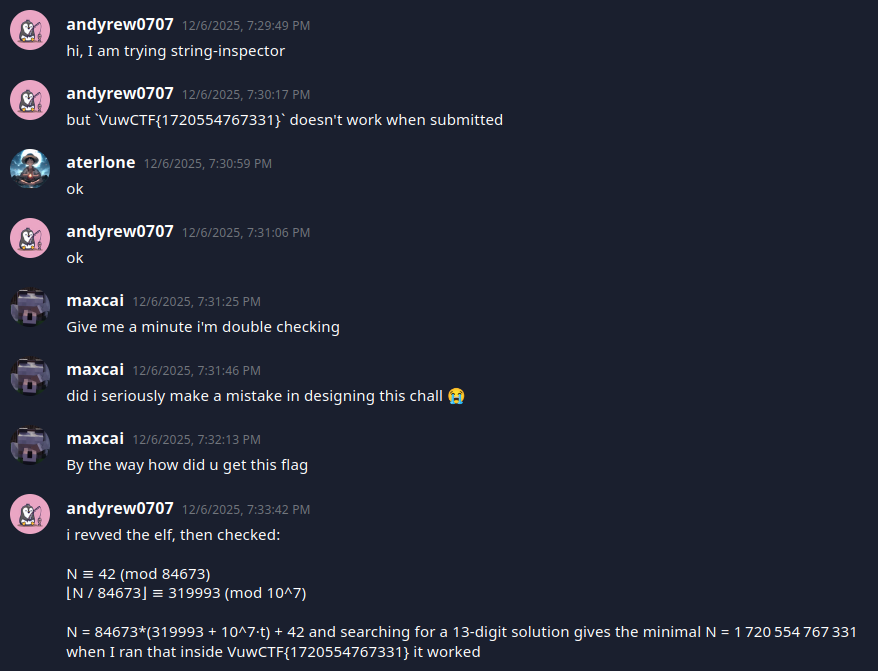

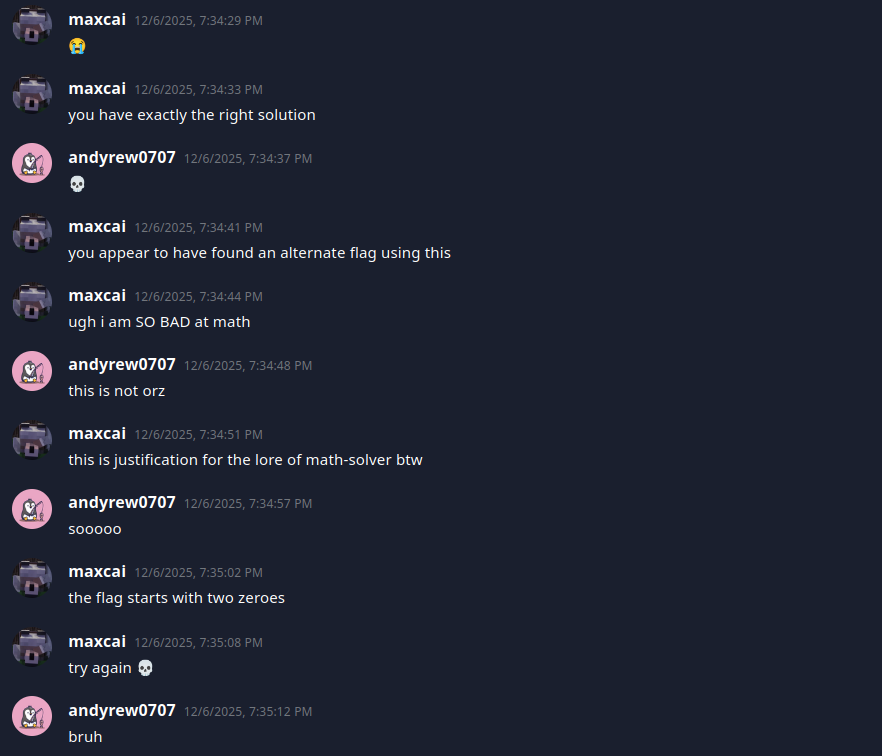

After a few crash outs, I made a ticket. I’ll let the conversation speak for itself:

This confirmed I did solve it correctly, but I had an alternate flag. Max, if you’re reading this, in the future please include all possible flags as correct answers 😭

At least now, I knew the intended flag “starts with two zeros”. Well, now I knew what the flag was. Trying the only answer with two leading zeros:

./inspector VuwCTF{0027094767331}

# Flag accepted!

That was the official flag! The final flag was: VuwCTF{0027094767331}.

Other than both Max and I losing some braincells, it was a pretty fun challenge!

Takeaways

- Start with the easy triage:

file,strings, andstracecan reveal control-flow tricks (here, self-execve) before you open a disassembler. - Even stripped static binaries leak constants in

.rodata; spotting ASCII gives you the targets to aim for. - If a checker treats input as a string, leading zeroes can produce multiple “valid” answers. If a platform rejects your locally accepted flag, consider the exact formatting the code expects (and don’t hesitate to make a ticket for clarification).

Thank you for reading my write-up! This was an extremely fun CTF, and I would like to express my appreciation to the organizers for hosting the CTF!

If there’s anything you think I could improve on in future write-ups, please let me know!

Thank you and have a great day!